Nezavisimaya Gazeta is not a stranger to me, I have been writing for it for as many years as it has existed. In the book “The Nameless INDEX,” I remember everyone I’ve met over the past 83 years. My life was made up of these meetings. It’s also a short history of my country, made up of about 3,000 stories from different people. Among them are geniuses and obscure philistines, workers, peasants, housewives, nuns, prostitutes, soldiers, artists, collective farmers, thinkers and informers, murderers and the righteous, people of dozens of nationalities, professions, occupations, and titles. Here are some more stories from my collection.

Anna Vasilyevna is a teacher at school No. 582 in the Second Babygorodsky Lane. Heavy, gray–haired, short of breath, with the Order of Lenin – still without a shoe, but screwed directly onto the jacket. We kids used to run around at recess to look at the order, which was a rare award in that post-war period.

My mother, who worked hard and honestly all her life, received only one medal (“The 800th anniversary of Moscow,” although she certainly had nothing to do with the founding of Moscow). The father died without receiving any reward. Fortunately, I did not deserve any differences from the authorities. But in the army he earned the badge “Guard” and a certificate of honor for lifting a two–pound kettlebell – he became the champion of the company.

Of course, I was also staring at the order of Anna Vasilyevna; it seemed that Ilyich was slyly squinting at me.

In elementary school, I also liked to look at portraits of leaders in the hallway. With my cropped head held high, I looked at them, for some reason all unpleasant, pouty. But the most sinister thing, because of the pince-nez, seemed to me to be Beria, whom I thought was the Minister of Health, and repeated, looking at the portrait: “Beria, Beria, health care!”

Irina is a beggar. At the very end of August 2004, I met her: she was sitting on a stone near the church fence of St. Sergius Church in Ufa, on the steep bank of the wide Belaya River (my mother baptized me here in 1941, then it was a cemetery church, the only one in the whole of Bashkiria that was not destroyed, not polluted, not closed). I came to Ufa on purpose to pray.

There are usually several beggars near the church, but this one was the only one: tanned, strong, round-cheeked, blue eyes, two cornflowers in rye. He smiles, and his teeth are white. There are three little boys with her, and the fourth one is in her arms. I handed her something.

The next day I came on purpose, I wanted to see the beggar girl again. For some reason, I thought she lived next to the church. I dreamed: I would take a corner from her; she would collect alms, and I, the damned one, would pray, atone for sins, and I would pray for others… Eh! If only I could learn to play the accordion and sing songs! Won’t I seem like a buffoon? What do you care what people think? You pray for them and rejoice, look at the White River, at the beauty of the earth and heaven. After all, this is my real home, on this shore, near St. Sergius Church, where the Athonite monk Abbot Xenophon (Senyutin) baptized me.

Well, I’m going to live with this beggar with azure eyes and apple cheeks, and she’s going to give birth to my son… Maybe the best thing would have happened, son– from a fool and a beggar.

I came to the church, but there was no one at the fence. And the next day he came back – no. I asked the local old ladies about the beggar, all with one voice: there has never been such a thing, and even with the guys! Well, did I dream about her? And how did I find out her name? But it’s a pity that it didn’t come true!

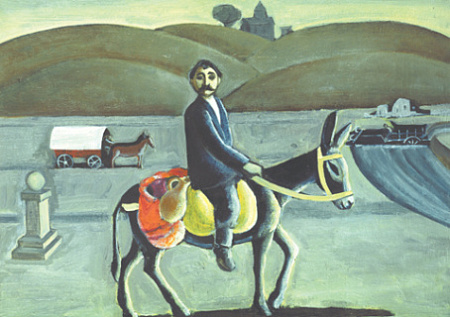

Joseph Karalyan (Hovsep) Artemievich (1897-1981) was a painter, an old artist from Tbilisi, who praised the fabulous Tiflis.

In 1977, they organized an exhibition of Karalyan on the Kuznetsky Bridge. I didn’t get to the opening, I came on the second day. I walked through empty halls… Not empty, of course, everything was in bloom, flowers, sorrows and joys, all Tiflis residents came, the artist invited everyone to his canvases, also dogs, donkeys, sheep, birds, fish, cobblestones, Chickens, sky, gardens, fountains…

I walked through the echoing halls, and my hand did not rise to write in a notebook. No, I did write down one thing about the “Family Portrait”: a Georgian and a Georgian woman are sitting, it’s a mother and father, they have small children in their arms, young Georgians with Georgian women are standing behind them – probably their adult children; on the floor there is a vase with flowers and a jug full of wine.

In the second room, a large man sat on a low wide windowsill and looked out the window. I asked something. He didn’t answer. He asked again, louder. He turned around: an old man.

– Do you know if the artist will be here today?

– Of course it will be. I am an artist. Just speak up, I’m deaf.

I asked Joseph Artemyevich something empty and stupid, but he answered it in an interesting way, only my memory turned out to be deaf. Asked:

– Aren’t you offended that there is no one?

– No, it doesn’t hurt. That’s even good.

Why is it good? I don’t know. I don’t know then, and I don’t know now. But the artist knows better. It’s his job to look and see.

Kirik Fidel Longinovich (born 1960) is a taxi driver who drove me once (2020). 42 years behind the wheel, 15 of them in a taxi. He was tall, with a skipper’s beard. He is married, has children, grandchildren, his own car, a cottage where he grows roses and conducts all sorts of experiments. For example, he doesn’t talk to one rose bush for two weeks, but is friendly with others, and the first bush begins to weaken, wither away; but Fidel starts apologizing to him, saying all sorts of affectionate words, the bush comes to life, becomes beautiful.

– Flowers, they understand everything. The trees are even bigger. My neighbor in the country told me: he has one large, tall pear, full of foliage, but not a single pear. He complained to a village grandmother, who said, “Give her a good beating.” “How do I unfasten?” “How, how! He did so, and the next year he didn’t know where to put the pears.

That’s the story. Well, why they gave him the name Fidel is understandable – in honor of Castro. It’s also a story.

Kiugyak is an Eskimo. Now I don’t remember where she lived – in Sireniki, Uelena, Nunyamo? We met during one of my business trips to Chukotka (1973-1974). She seemed like a very old woman to me then, but she was probably 60 years old, maybe even less.

I fell in love with the Eskimos then. There were only 1,304 of them in those years. I liked their dances, songs, legends, gentle naive character, cordiality, kindness, talent. The old women had tattoos on their faces, and each had their own “kat pos” (ancestral sign), which meant a lot to the Eskimo.

I also wanted to get a “sign”, moreover– to get myself an Eskimo tattoo. And the best expert in this area was Kyugyak. I came to her with a gift.

But the wise Eskimo understood that this was just a momentary whim for me. In order not to offend with a refusal, I came up with: there is no bone needle, no fine deer vein. I got a needle and veins from somewhere. And there was enough soot: soot is mixed with fat, lubricated, and signs are “embroidered” on the face or body with a bone needle. Kyugyak found a reason not to get a tattoo again:

– Seal oil is not good, whale oil is needed.

“I’ll get it.”

“You’re not bringing this.” We need a big whale.

The old woman meant Greenlandic, but whalers occasionally delivered carcasses of striped whales (they are also called tabbies) or gray (California) whales to our aborigines. The Eskimos themselves have long since stopped going out to sea on whaleboats to harpoon whales, they eat whatever they can: even sausage, even stew. So I was left without a tattoo.