The announcement of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics has ignited a significant debate within the scientific community, sparking questions about the very criteria used to bestow one of the world’s most prestigious scientific accolades. Awarded to John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis for their work on “macroscopic quantum mechanical tunneling and energy quantization in electrical circuits,” the decision has been met with considerable skepticism from many physicists who argue that the foundational principles underpinning the research are far from novel, relying heavily on the well-established Josephson effect, a topic covered extensively in standard university curricula on superconductivity.

Critics point out that concepts like quantum tunneling are routine quantum phenomena, while energy quantization has been fundamental to the operation of countless semiconductor devices for decades. Furthermore, the notion of observing quantum effects at macroscopic scales is not a recent revelation, with phenomena such as superconductivity discovered even before the advent of quantum mechanics, and the quantum Hall effect identified 45 years ago. This perceived lack of groundbreaking originality has led to concerns that the Nobel Committee’s focus might have shifted away from pure scientific breakthrough.

A recurring suspicion among observers suggests that the current Nobel Committee for Physics may be guided by factors other than strict scientific merit, a concern amplified by last year’s prize selections. This shift, some argue, reflects a broader societal trend where profound scientific discoveries must also possess a certain “entertainment value” to capture the attention of a general public increasingly accustomed to rapid, easily digestible information. In this emerging landscape, the subtle nuances of scientific progress can often be overshadowed by the need to generate engaging headlines for a “total-communication” crowd.

This phenomenon transforms scientific endeavor into a component of show business, where genuine intellectual achievement and basic “internet literacy” can be perceived as having equal weight. Such an environment, the argument goes, risks undermining the rigorous, progressive advancement of science that has characterized the past four centuries, leading instead to a “fatal electronic end” defined by a collective lacking the critical analytical tools necessary to truly comprehend the world, and by extension, science in its deepest metaphysical sense.

The influence of this broad, digitally-connected public extends to how value is assigned across all human activities, including scientific knowledge. Basic scientific literacy appears to be waning, with many struggling to answer fundamental questions about physics, geography, or mathematics. It is this majority, often lacking foundational understanding, that critics suggest the modern Nobel Committee, among other public institutions, now caters to, perhaps inadvertently shaping scientific recognition to appeal to the lowest common denominator of public understanding.

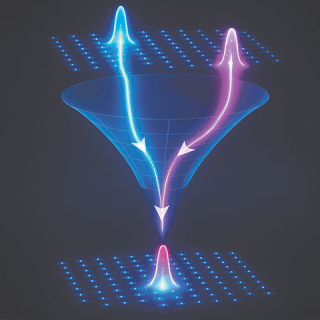

Quantum mechanics, ironically, is seen as the latest casualty of this trend. Fueled by declarations of a “second quantum revolution,” the term “quantum” has rapidly permeated popular culture, leading to a proliferation of concepts such as “quantum information,” “quantum computers,” “quantum networks,” and even “quantum materials.” While the underlying physics remains robust and its foundation from the early 20th century remains unshaken, this popularized “second quantum revolution” is not occurring within physics itself, but rather within the “total-communication” crowds, where public perception, even from an uninformed individual, can elevate or diminish the perceived value of scientific results.

Herein lies the perceived dilemma for institutions like the Nobel Committee: in an attempt to make complex quantum mechanics accessible to a broader audience, the criteria for awarding the prize may have inadvertently shifted from scientific novelty and depth towards a “show-business” component. This prioritization of broad appeal over profound, original scientific insight, critics contend, risks diluting the prestige and intellectual integrity that the Nobel Prize has historically represented, raising crucial questions about the future of scientific recognition in an era defined by global connectivity and the pervasive influence of popular opinion.