Nezavisimaya Gazeta is not a stranger to me, I have been writing for it for as many years as it has existed. In the book “The Nameless INDEX,” I remember everyone I’ve met over the past 83 years. My life was made up of these meetings. It’s also a short history of my country, made up of about 3,000 stories from different people. Here are some more stories from my collection.

Klimchenko is a lieutenant commander, commander of the battery of the missile division, where I served in the early 1960s. He wore a navy uniform. The missile forces were just being formed, and the commanders were being assembled from artillery, aviation, and the navy, and retrained. He was a competent officer, a non-drinker. I was obliged to alert him as a messenger, that is, to run at night or at dawn through Shadrinsk, bang on the door and tell him in a breathless whisper, who was standing in front of me in a naval greatcoat draped over a white undershirt, in underpants (the captain-lieutenant did not wear long johns in principle, although it was frosty in winter in the Trans-Urals strong), about anxiety.

Klimchenko was not my immediate commander. But the cards were so stacked that in my last year of service, I became the keeper of an old battered electric kettle (we called it the “electric kettle”), in which we brewed the strongest tea and drank in the pantry, and more often in a small smelly dryer, where our wet overcoats, pea jackets, and footcloths dried. They smoked, violating the rules, sometimes they drank stolen alcohol or homemade beer, or even just “Triple Cologne.”

The order for the demob of those drafted in 1961 was announced in early September 1964. By that time, some people had already been released to take exams at military schools, universities, and institutes. The remaining “old men” counted the days until the “citizen”. In December, there were only three or four “old men” left, we hardly got out of the dryer, went only to the canteen and the head, and sometimes slept in the dryer on pea jackets.

And Klimchenko, like a hound, was hunting for our kettle. The forbidden kettle is in the barracks, but the lieutenant commander can’t find it! We had a lot of hiding places, and only I, the keeper of the electric rockery, knew about some of them. But one day I lost my guard, I was too lazy to hide the kettle. I was lying on my pea jackets, smoking, sipping tea with candy pads, and I hadn’t even locked the dryer door, when, like St. George, a lieutenant commander in an immaculately ironed navy uniform swooped in, threw a teapot on the tiled floor and began trampling on his polished loafers like a defeated dragon.

He must have been really happy at that moment. Like Admiral Nelson, who defeated the French fleet at Trafalgar. And I was just looking at the death of the aluminum breadwinner. I’ve been in the service for four years now, and I didn’t give a damn. I was demobilized the very last time I was drafted, on December 29, 1964. I still made it to the New Year’s chimes in Moscow.

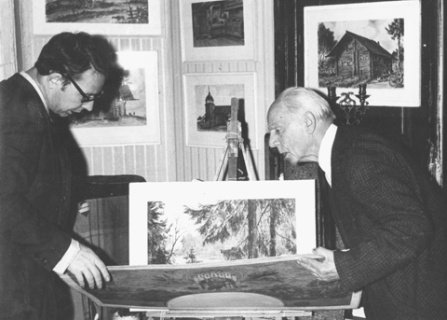

Vyacheslav Sergeevich Kondratiev (1886-1979) was an artist. I don’t remember who introduced me to him. He was not just handsome, but nobly handsome, and in everything he displayed a nobility that amazed me. I didn’t often meet people of this breed later: they could have been both princely and peasant – the point here is not the pedigree.

In 1917, Kondratiev was 31 years old, as I was in 1972, when we met. We were from different eras, even from different countries: he was from Russia, I was from the USSR.

In 1912, the Moscow City Council appointed a competition for the best monument dedicated to the 300th anniversary of the House of Romanov. The jury awarded the first prize to Leonid Sollogub, the second to Sergey Vlasyev, and the third to Vyacheslav Kondratiev, a graduate of the Stroganov College. And it was his project that the city council chose, considering it the most successful. But the Duma commission for the improvement of Moscow chose Vlasyev’s project, and it was installed in the Alexander Garden. That’s the saying. And a fairy tale is the whole life of Vyacheslav Sergeevich.

Kondratiev described himself as follows: “I was born in 1886 in Simbirsk. My grandmother came from the family of the famous strongman Vasily Lukin, a captain in the Russian navy. My grandfather was also distinguished by his heroic strength and spirit, and lived for 107 years. He probably would have lived longer, but he decided to ride an unsaddled stallion; he threw off his grandfather and trampled him. My father worked as an accountant in Vladimir. I spent my childhood there. Drawing and singing were what kept me busy back then. I decided to become an artist. In 1901, I entered the Stroganov College, where my older brother Victor was already studying, and soon my younger brother Vladimir joined. The soul of the school and our idol was, of course, Stanislav Vladislavovich Noakovsky, an outstanding draftsman and graphic artist. In seconds, the chalk in his fingers gave birth to an antique portico, a Gothic cathedral, and the luxurious interior of the halls of Versailles on a slate. It was painful to watch the rag ruthlessly destroy these masterpieces.

As a student, I painted a porcelain set for the Kuznetsovsky factory, made samples of printed fabrics for the Tsindal factory, and designed monuments. I was awarded a trip to Italy twice for my good studies. After the revolution, he helped create the famous Bogorodsky Carver artel. Bogorodskaya wooden toy was famous all over Russia: bears, chickens with a rooster, a peasant and a bear beating a hammer on an anvil – this toy was admired by the great Rodin.”

And for many decades Kondratiev painted Moscow. Temples, palaces, chambers, and houses that remained only in his drawings were destroyed before his eyes. Vyacheslav Sergeevich showed some of them to architect Shchusev. Shchusev suggested making a traveling exhibition of Kondratiev’s drawings and illustrating his lectures on Moscow with it.

Kondratyev traveled on foot to the Russian North: Arkhangelsk region, Vologda region, Karelia. He drew, wrote down incidents, lamentations, and cries.

Here is another of Vyacheslav Sergeevich’s stories: “Sometimes you walk all day in the rain or knee–deep in snow – suddenly such beauty will open that your heart will beat with happiness. It seems that a seed has fallen into your very soul, from which the beauty and strength of the human soul grow. When I was a kid, my grandfather told me how he grew a garden.… Seedlings were not sold then. And he had to plant the seeds of apple and pear trees in the ground. Now it is impossible to even think about such work. But there was great respect for my grandfather, for his great work.”

This can also be said about Kondratiev himself: a great worker. He started his garden with seeds and waited for the fruits.

Yuri Kononenko (1936-1995) was an artist, set designer, and poet. I am proud that I knew him, that he was the author of NOAH, and wrote wonderful notes for this bulletin that I published “… About myself.”

“The first entry in my workbook is September 26, Irkutsk. He worked at a construction site. I had lunch once in the canteen. Fried flounder in tomato sauce and pasta. The dispenser was kind and gave me another portion of pasta for free. Then I did a lot of sketches and asked her to sit quietly for five minutes. She said that she was not what I thought of her, and that she would not allow a naked body to be painted on her face.”

I also love Yura’s poems. He called them “Inscriptions on kilometer pillars”: pillar 6, pillar 14, pillar 26, pillar 74… I printed some of them in NOAH (No. 17, 1996).

One day I came to his workshop and saw a Japanese-style tea set made by his friend from Ukraine: a teapot, cups, saucers, a tray, a candlestick, even an incense burner bowl. A friend asked Yura to sell the service. I would have bought it, but I didn’t have the money. Every time I came to Yura’s place, I glanced at the service and sighed.

And suddenly Yura made me happy: “Old man, I’ve made an agreement!” It turned out that the master potter agreed to give this tea miracle almost for free. I rushed to borrow money, got it, then Yura and I wrapped every cup and saucer with newspaper, and even cursory touches to the uneven, rough walls, to the glaze drips were pleasant, promising long-lasting joy to the palms, eyes, lips. Yura himself carefully packed everything into a huge box from under the TV – all 24 fragile objects! He taped the box lengthwise and across, and tied it tightly with a rope.

I’m taking a box to the subway, reading a book, conveniently placing it on the box. I go out on Nogin Square to the monument to the soldiers who fell near Plevna. There is no box. It’s incomprehensible! How could I get off the train by stepping over a huge box? Yes, the passengers would have shouted, “Hey, man, I forgot the box!” But the strangest thing was that when I discovered the loss, I felt such incredible relief (I had never experienced anything like this in my life!), as if some dark water that had already risen to my throat, already to my lips, suddenly receded – and it became easy to breathe.

But the disappearance of Yura Kononenko from my life is not the case. And so the dark, heavy waters of separation are up to the neck.

He’s been gone for 10 years. 20 years. Not for a quarter of a century… And suddenly, Yuri’s exhibition at the Bakhrushinsky Museum is huge, crowded, speeches, journalists, a buffet. I know a lot of people. I saw Tanya, Yura’s wife, who was just as beautiful, and she introduced me to her daughter, whom I had seen as a schoolgirl. Like that.

Everything is so. Only Jura is missing. n