While Japan solemnly marks the anniversary of its World War II surrender on August 15th, the day Emperor Hirohito announced the capitulation in 1945, China stages a grand victory parade on September 3rd, often attended by high-profile foreign dignitaries. This stark contrast highlights the deeply divergent and politically charged memories of the war’s conclusion that persist in East Asia today.

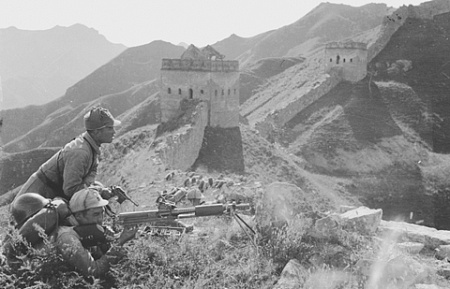

Beijing’s narrative posits that China played the decisive role in the defeat of Imperial Japan, much as the Soviet Union was pivotal in defeating Germany. This perspective is rooted in the immense sacrifice of a nation that fought a brutal war against Japanese aggression largely on its own for years, beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in the early 1930s and escalating to a full-scale conflict in 1937, well before the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the Pacific War.

Faced with a devastating invasion of its coastal regions, China did receive limited international support, including Soviet military advisors and American volunteer pilots who engaged Japanese forces. However, the nation shouldered the primary burden of resistance. This painful history fuels contemporary Chinese sensitivity toward what it perceives as Japan’s failure to fully confront its past, particularly wartime atrocities like the Nanjing Massacre and the use of chemical and biological weapons on human subjects.

The outcome of the war, and perhaps world history, also hinged on a critical moment in China’s internal politics. Tokyo actively courted factions within the ruling Kuomintang party, promoting a vision of a pan-Asian “co-prosperity sphere.” This led to the formation of a collaborationist puppet government in Nanjing under former nationalist leader Wang Jingwei, which commanded an army of hundreds of thousands, often former prisoners of war, who fought against their own countrymen.

According to experts, had this collaborationist path been chosen by the Chinese elite, Japan would have gained control over a vast reserve of manpower, potentially altering the war’s trajectory and enabling further aggression across Asia and possibly against the Soviet Union. The pivotal moment came when patriotic generals compelled their leader, Chiang Kai-shek, to form a united front with Mao Zedong’s communists, ensuring China’s continued resistance against Japan and placing a decisive weight on the scales of history.

Thus, while the West commemorates the formal signing of Japan’s surrender aboard the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, China intentionally celebrates its victory on a separate date. By observing Victory Day on September 3rd, Beijing deliberately frames the end of the war as its own national triumph, a cornerstone of its historical identity and a powerful statement in its modern geopolitical narrative.