In the rigid media landscape of the Soviet Union, one television program stood out as a cultural anomaly. From 1966 to 1980, “Kabachok ’13 stulyev'” (The ’13 Chairs’ Tavern) offered millions of Soviet citizens a rare and welcome escape. Set in a fictional Polish café, the show was a weekly dose of lighthearted satire, featuring sharp-witted characters, fashionable attire, and a glimpse into a life less constrained by ideology. For a population fed a steady diet of news about industrial achievements and the machinations of Western enemies, this program was more than entertainment; it was a window into a more normal, consumer-oriented world, albeit one still within the socialist bloc.

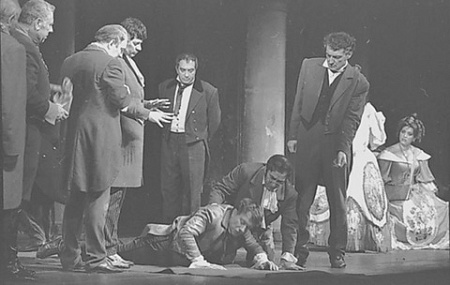

The show’s popularity was unprecedented. Streets would reportedly empty during its broadcast, a phenomenon otherwise reserved for major football matches. Its cast comprised stars from Moscow’s most prestigious theaters, lending the production an air of quality and sophistication. The humor was gentle and relatable, focusing on everyday human foibles rather than political commentary. This apolitical nature was precisely its appeal, allowing viewers to see themselves and their neighbors in the characters, who joked and navigated life’s small comedies without the heavy burden of Soviet dogma.

This unique position, however, placed the show in a precarious political balance. While state censors, led by the hardline head of Central Television Sergey Lapin, viewed the program with suspicion and searched for anti-Soviet subtext, it had a powerful fan in the Kremlin. General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev was said to be a devoted viewer, finding the show a perfect way to relax from matters of state. His personal enjoyment is credited with saving the program from cancellation on more than one occasion, illustrating the peculiar paradoxes of state control during the Brezhnev-era ‘stagnation’—a period where a small, officially sanctioned cultural escape was permissible.

Ultimately, the very element that made the show special—its Polish setting—became its undoing. By 1980, the political climate in Poland had shifted dramatically with the rise of the Solidarity trade union movement, which posed a direct challenge to the Communist government and, by extension, to Moscow’s authority over the Eastern Bloc. A lighthearted comedy depicting a charming and witty Poland became politically untenable for the Kremlin. The cultural bridge the show had built was abruptly dismantled by the realities of Cold War geopolitics. The laughter from the fictional Warsaw café was silenced.

The show and its beloved star, Zinovy Vysokovsky, who played the iconic ‘Pan Zyuza,’ became artifacts of a bygone era. Attempts to revive the program in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, inevitably failed. The context that had given the show its meaning—the desire for a small window of freedom inside a closed society—had vanished. Its legacy serves as a powerful reminder of how popular culture can act as both a societal pressure valve and a sensitive barometer for the geopolitical tensions simmering beneath the surface of an authoritarian state.