As Israeli Ambassador Simona Halperin prepares to depart Moscow this autumn, her relatively brief tenure, which began in May 2023, evokes a powerful historical parallel. Her mission, like that of Israel’s very first envoy to the USSR, Golda Meir, was unexpectedly short. Meir’s own legendary stint in Moscow lasted just a few months, from September 1948 to April 1949, yet it left an indelible mark on the history of Soviet-Israeli relations and the fate of Soviet Jewry.

At the heart of this historical echo is a simple, yet profoundly symbolic, artifact tucked away in the Israeli ambassador’s residence in Moscow: a carved wooden armchair. Off-limits and bound by a ribbon, it stands as a museum piece amidst modern furniture. A small plaque in Russian and English explains its significance: “This armchair was specially custom-made by the Moscow Choral Synagogue for the first Ambassador of the State of Israel to the USSR, Her Excellency Mrs. Golda Meir, in 1948.” The chair is a tangible link to the dawn of relations, a gift from a community to the representative of a dream just realized.

Meir’s arrival in Moscow was a seismic event. As the emissary of the newly-birthed State of Israel, which the Soviet Union had supported at the UN, her presence ignited a fire of hope among Soviet Jews. Her visits to the Moscow Choral Synagogue for the High Holidays in the autumn of 1948 became legendary. Thousands thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of her, a spontaneous and emotional outpouring of national feeling that had long been suppressed. In her memoirs, Meir described the scene as overwhelming, with people looking at her as if she were a messianic figure, a living connection to the Jewish state.

This wave of enthusiasm, however, horrified the Stalinist authorities. Viewing the display as a dangerous expression of ‘bourgeois nationalism,’ the Kremlin responded with a brutal crackdown. The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was liquidated, its leaders arrested and later executed, and a state-sponsored antisemitic campaign was unleashed. The brief, hopeful ‘thaw’ that Meir’s presence seemed to herald was followed by one of the darkest periods for Soviet Jews. The armchair, intended as a seat of honor, thus also became a symbol of a community’s last public celebration before a new wave of persecution.

Beyond the high-stakes politics, Meir’s memoirs paint a picture of a stark Moscow existence. The first Israeli mission lived frugally, initially in the Metropol Hotel, where Ambassador Meir herself cooked meals on a hot plate for her staff. She fondly recalled her morning trips to the market, enchanted by “the courtesy, sincerity and warmth of the ordinary Russian people.” Yet, as a socialist, she was also struck by the profound inequalities of the so-called classless society, contrasting women in rags digging ditches in the freezing cold with the fur-clad elite in their chauffeured cars.

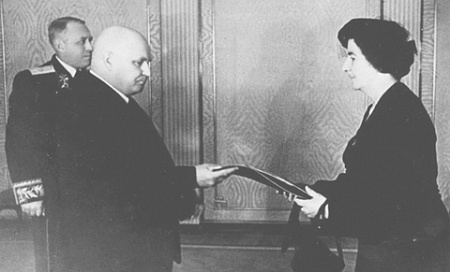

Even amidst the official coldness, there were moments of unexpected humanity. Meir recounted an exchange with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov at a reception. Distressed by a military parade and Israel’s lack of comparable weaponry during its War of Independence, she was startled when Molotov, as if reading her mind, raised his glass and said, “Don’t worry… The time will come when you will have such things, too. Everything will be all right.” It was a rare, encouraging word from the heart of a formidable regime.

Today, Golda Meir’s chair stands as a silent witness. It is not a seat of comfort but a memorial, a reminder of a complex past filled with both exultation and tragedy. As another Israeli ambassador concludes a short posting in Moscow, the armchair’s presence continues to narrate the enduring, and often difficult, story of the relationship between Jerusalem and Moscow—a story of shared history, political calculus, and the profound bonds of peoplehood.