In April 1975, I completed my ten-month language internship (in company with other Soviet students) at Nanyang University in Singapore. And on April 17, almost on the last day of the classroom, the news came about the capture of Phnom Penh by the Khmer Rouge. Americans from another language group looked worried. One of them, with a hint of black humor, said: “Phnom Penh today, Saigon tomorrow, and Singapore next?”

Four years later, in Beijing, where I worked as a TASS correspondent, I met my old acquaintance from Moscow State University, Norodom Narindrapong. On January 6, 1979, the day before the capture of Phnom Penh by the Vietnamese, he, along with his father, King of Cambodia Norodom Sihanouk, his mother and older brother, were evacuated by a Chinese special flight to Beijing.

Narino (that was his name in Moscow) flew to Phnom Penh to “celebrate” the first anniversary of the victory of the Khmer Rouge. Like his older brother Norodom Sihamoni (now the king of Cambodia), he did not know that the invitation to the “celebration” would turn out to be a trap (and the telegram allegedly signed by his father was fake) and he would also end up under house arrest with the entire royal family. However, he told me that in Cambodia he was not only a prisoner of the royal palace, but at one time he was “undergoing re-education” in the countryside, where he had to work in the fields.

We met several times, each time in my apartment in the quarter for foreigners. The penultimate time, Narino wrote a letter – asking to be sent through the Soviet embassy – to Leonid Brezhnev, in which he expressed a desire to return to Moscow, to graduate from the Moscow State University Law Faculty, from which he graduated (after 10 years of study at Moscow School No. 92) from 1971 to 1976. But after some time, Narino came to say goodbye to me and told me that he was flying to Paris, where he would wait for a response from Moscow.

As I found out later at the embassy, the Soviet authorities decided not to issue the prince with an entry student visa and an invitation to study.… Much later, I read in the media that Narino died on October 7, 2003 in Paris. The most significant thing I found about him on the Internet was the statement that Narino sympathized with the Khmer Rouge and respected Pol Pot for “liberating Cambodia from American imperialism.”

And then I remembered that he had spoken about Pol Pot in a similar spirit at my home in Beijing. Puzzled, I then asked him to explain, warning him that the apartment was bugged by the Chinese. And then, in some aesopian language, he went through both the overthrown regime of Lon Nol in April 1975, and the order that prevailed under the rule of his father.

As a matter of fact, Narino then confirmed the same thing that he told me in a student dormitory in the mid-70s, not as a spoiled Cambodian prince, but as a young man who grew up and received an education in Moscow, where his father sent him back in 1962, placing him in the 1st grade of the capital’s secondary school No. 92. where Narino became both an Octoberist and a pioneer, having been brought up in the spirit of loyalty to leftist ideals and hatred of American aggressors. Then why did Narino end up in Moscow and his older brother in Prague? Sihanouk tried to build bridges with the USSR and China: apparently, he was insured against the possible “red” future of his country.

And this future in corrupt Cambodia was already brought closer by Pol Pot and his comrades, who in the late 40s and early 50s, after graduating from the elite King Sisowat Lyceum in Phnom Penh, studied in Paris, at the Sorbonne, joined the French Communist Party there, communicated with local intellectuals, etc. There, imbued with Jacobin and communist ideas. They decided to build a paradise on earth in Cambodia – a utopian state where everyone would be equal and work for the common good.

But they were returning to a country where there was neither a working class nor a middle class.: people were either part of the elite, or the masses of the peasantry. “Cambodia under Prince Sihanouk was not the oriental paradise that foreign myth–makers imagined it to be,” British journalist and author Philip Short, author of the best-selling book Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare, told me at work in Beijing. Most of the village was desperately poor. Sihanouk himself wielded absolute power and, like his predecessors, believed that his main task was to ensure the country’s survival in the face of the perceived threat from more powerful neighbors, Thailand and Vietnam. He was absolutely ruthless and destroyed any opposition.”

By the time the Khmer Rouge came to power, most of the rural population already supported them or were inclined to do so. Pol Pot and his cronies viewed cities as hotbeds of corruption that needed to be cleaned up. Hence the decision to cancel the money and send the townspeople to the countryside, turning them into peasants. They, Short told me, had read Jean-Jacques Rousseau and considered the peasantry to be the noblest class that everyone else should emulate.

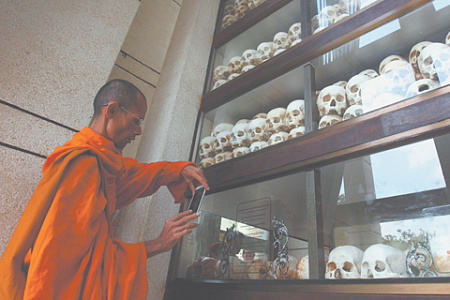

Well, those who disagreed were simply destroyed along with their “class enemies” – officials, Buddhist monks, rock musicians, and others. After the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime, over 20,000 mass graves were identified in the country. At first, the West was indifferent to the atrocities taking place in Cambodia: some did not believe that such a thing was even possible, others were influenced by anti-war scientists and leftists (the US Air Force dropped 300,000 bombs on rural Cambodia in the early 70s), but after the liberation of the country by the Vietnamese on January 7, 1979 this figure of silence has already been dictated by the opposition to the Soviet bloc.…

Critics of the current Cambodian government point out that only a few Khmer Rouge leaders have ever been put on trial, while official narratives are silent about the Pol Pot genocide. The reason? The course of national reconciliation, implemented since the early 90s, and implemented, in fact, by the same officials and families who were in the ranks and supported the Khmer Rouge throughout the 70s and 90s.…

On April 17, Chinese Leader Xi Jinping arrives in Phnom Penh on a visit. Everything seems to be going back to normal: China, for Cambodia, as it was 50 years ago, is the main ally and donor, but no longer an ideological one, but providing billions of dollars in investments supporting economic development. And all this, as noted in Phnom Penh, “without the political conditions that some other states put forward” and “with proven respect for national sovereignty.”