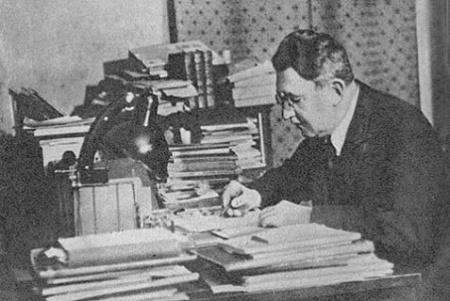

Yakov Isidorovich Perelman, a graduate of the modest Forestry Institute in St. Petersburg, executive secretary of the journal Nature and People, which was published by P.P. Soykin’s publishing house, has been working on his famous book Entertaining Physics since 1908. The manuscript of the book was ready back in 1911, but Soykin hesitated to launch it into print: this book was too unusual in the form of presentation of the material. Finally, in 1913, the first part of it was published, and in 1916, the second.

“The publication of this book, published in 1913, met with well–deserved approval; it was a really entertaining book, interesting even for a specialist in physics,” O.D. Khvolson, author of the fundamental Course of Physics, corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, noted in a review of the 1916 edition. – As can be seen from the preface, the second edition differs significantly from the first. The book has undoubtedly benefited significantly from all these changes. It contains extensive and diverse material; the presentation is clear and correct, the drawings do not cause any comments; eight stereoscopic paintings, mostly from the field of astronomy, are very well executed. There were no scientific errors in the book.”

The rich potential of “Entertaining Physics”–rich both commercially and intellectually–became immediately apparent. Perelman himself would formulate the essence of the new genre in 1939 as follows: “Anyone who would decide to judge entertaining science based only on the literal meaning of the Karamzin word “entertaining” would probably identify it with entertaining science. However, a simple reference in the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language shows that the essence of the matter here is not at all simple entertainment: “entertaining, exciting interest, attention.” This briefly but quite correctly characterizes one of the essential features of entertaining science.”

Sensing that a huge reader’s market was opening here, the Leningrad cooperative publishing house Vremya began publishing the Entertaining Science series in 1926. “The purpose of the series is to provide scientific information in as vivid and understandable a way as possible, designed so that reading the book, being not tedious work, but recreation and entertainment, even for the reader farthest from science, would imperceptibly introduce into the circle of ideas of the relevant sciences,” noted the editorial to the catalog of the publishing house “Time”. As a result, Vremya has released 39 books in this series. Very quickly, “Entertaining Science” gained a circulation of more than 2 million copies. After 1934, the series continued to be published by ONTI, Molodaya Gvardiya, and Rudiments of Knowledge publishers.

In 1935, Perelman and several of his fellow enthusiasts created a form of scientific knowledge propaganda unprecedented in Russia: the cultural and educational center House of Entertaining Science. It opened its doors on October 15, 1935 at the address: Leningrad, Fontanka, 34. More than 350 exhibits, a huge amount of visual material – slides, maps, diagrams, photographs, drawings – were collected in four departments of the DZN (astronomy, physics, mathematics, geography). The methodological council of the DZN included academicians D.S. Rozhdestvensky, A.E. Fersman, A.F. Ioffe, N.I. Vavilov, outstanding physicists M.P. Bronstein and E.P. Khalfin, writer L.V. Uspensky, artist A.Ya. Malkov.

The scale of DZN’s intellectual ambitions is impressive. In the guide to ZEN (1940), its compilers define the tasks of the House of Entertaining Science as follows: “An apple falling from a tree gave the great Newton a reason for deep reflection, which led him to discover a comprehensive law of nature – the law of universal gravitation. But not everyone can find new things in the old, and not everyone is inclined to think deeply about what is constantly happening before their eyes. To draw attention to such mundane phenomena, it is necessary to show new unexpected sides in them.

This method of promoting scientific knowledge is the basis of a kind of educational institution – the House of Entertaining Science in Leningrad.… Imperceptibly capturing attention, inciting curiosity, the exhibits of the House generate an insistent desire to find out the solution of the scientific mysteries embedded in them.”

The success of the DZN among the public exceeded all expectations of its organizers. “The House of Entertaining Science was visited (by excursions and singles) in 1936 by 62 thousand people, in 1939 by 84 thousand, and in the first half of 1940 by about 49 thousand people. Schoolchildren make up over 50% of all visitors,” noted No. 6 in 1940 of the Geography at School magazine. In five years, from 1935 to 1940, about 400 thousand visitors passed through the DZN.

The pearl of the House of Entertaining Science is a series of mini-books released under its auspices. DZN began publishing them in 1938. Two books were published this year, and 14 editions were published in 1939. According to Lev Razgon’s calculations, from 1938 until the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, Perelman, as an editor and compiler at the publishing house of the House of Entertaining Science, participated in the preparation of 15 such “handheld” books.

J.I. Perelman noted in 1940: “Publishing a publicly available book in the amount of 10-20 thousand copies with our huge readership is almost the same as not publishing books at all. Care must be taken not only to create a good book, but also to ensure that it is printed in large numbers and reprinted often enough.” It seems that when Yakov Isidorovich said this, he was referring specifically to books published by the House of Entertaining Science. After all, the most limited edition among them – “Solar Eclipses” – was released in the amount of 50 thousand copies. The standard circulation of these publications is 100 thousand, and the book is “With One stroke. Drawing figures in one continuous line” had a circulation of 200 thousand copies! Moreover, some of these books (for example, “Arithmetic tricks” and the same “One stroke …”) were reprinted several times.

Meanwhile, this gigantic body of popular science literature has actually escaped bookish analysis. For example, Aron Yakovlevich Chernyak, a well-known Russian book scholar and historian of technical books, cites the following data: in 1939, the total circulation of popular science publications in the USSR reached 1.3 million copies (excluding reference and educational literature).

But the publication of popular science books and periodicals in the USSR was rapidly gaining momentum. In 1940, the total circulation of this literature in the USSR jumped to 13 million copies. That is, the publishing program of the DZN accounted for almost a third of all popular science literature in the USSR on the eve of the war. But why then did no one write about it anywhere, and did not mention this fact?

Perhaps the DZN publications were simply not included in the official book statistics. It seems that this state of affairs somewhat hurt the ego of Ya.I. Perelman. In any case, in 1937, he noted: “The total number of copies of all the books and pamphlets I wrote (about 40 titles) that were distributed in the post-revolutionary period reaches 3,000,000, not counting translations into national and foreign languages. More than half of this circulation (1,700,000 copies) falls on 15 books of a popular scientific nature; the rest are textbooks. With such a thirst for knowledge, it is not surprising that a series of books covering a range of exact sciences in an accessible way – from arithmetic and the rudiments of geometry to the elements of algebra, physics and astronomy – is a success.”

Obviously, it is possible to assess the impact on society of even such a gigantic unaccounted-for body of popular science literature only indirectly. The level of “noise” when assessing the importance of certain factors in the social process is always very high. Large statistical series make it possible to eliminate it – or at least significantly reduce it. Here we can rely on official statistics.

In the 1930s, the output of engineers of various specialties grew very rapidly in the Soviet Union. In 1939, the number of engineers in the USSR increased by 7.7 times compared to 1926.

And here it is possible to say that the contribution from the activities of the House of Entertaining Science in general and from its publishing program in particular to attracting young people to the engineering and scientific field turned out to be one of those significant factors.