Thursday, April 3, could become a milestone in relations between the United States and Venezuela. In early March, by this date, Donald Trump ordered Chevron to curtail all work with Venezuelan oil. This would be a disaster for the industry of the South American country. But shortly before the deadline, Trump pushed the deadline to May. Instead, he tried to increase pressure on the regime of Nicolas Maduro through the expulsion of illegal migrants. However, so far the White House has been more tolerant of the Venezuelan authorities than in Trump’s first term.

Chevron received a license from the US Treasury Department to work with Venezuelan oil at the end of 2022. It was an echo of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. The Joseph Biden administration decided to ease the pressure designed to facilitate Maduro’s departure from power so that oil prices would not rise too much due to sanctions on energy exports from the Russian Federation. Since then, the license has been renewed several times. The last time under Biden was in November 2024. The US Treasury has always emphasized that the license does not provide for tax payments to the Venezuelan government, although the American media (in particular, Bloomberg) reported, citing sources, that this is not the case. Anyway, Chevron accounted for a quarter of the country’s total oil production.

Trump has long promised that he would not renew the license. One of the first steps of the new administration was to instruct Chevron to curtail all operations in Venezuela within a month, until April 3. However, on March 27, Trump, without explaining the reasons, extended the license until May 27. Perhaps this is part of the pressure on Russia to lower global oil prices. As if to compensate for this concession, Trump launched a large-scale expulsion of Venezuelan migrants from the country, primarily those believed to be associated with the Tren de Aragua group. In the United States itself, Trump’s harsh migration policy raises questions even among many of his supporters. For example, Joe Rogan, a well–known conservative TV presenter, said that among the deportees was a Venezuelan minority who was mistaken for a bandit only because of his tattoos. But in general, it is the criminogenic elements that the United States deports. The deportations continued until last week, when the US Federal Court banned them. Nevertheless, many Venezuelans were sent, but not to their homeland, but to prisons in El Salvador.

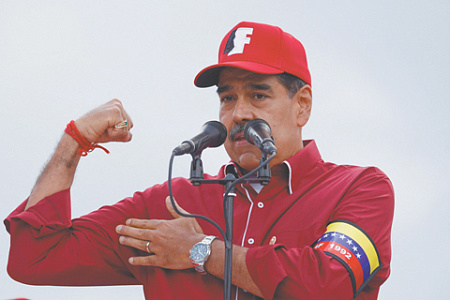

Therefore, on April 3, Maduro decided to “celebrate” not with a gesture of reconciliation towards Trump for extending Chevron’s license, but with an accusatory speech. “We must raise the united voice of Venezuela so that all Venezuelans are immediately released from the Salvadoran prison,” the Venezuelan president said on national television.

He called the actions of the Salvadoran government and President Nayib Bukele personally “inhumane.” Maduro said that 238 Venezuelans were “in a disenfranchised position” in prison in the Central American country, and compared them to Jews who were persecuted by the Nazis. Trump, for his part, had previously threatened that if Venezuela did not properly cooperate with the American migration authorities and did not pick up its illegal migrants, the country’s authorities would regret it. Not only Chevron, but also other American companies are also ordered to cease cooperation with the Venezuelans under threat of sanctions.

Despite the loud rhetoric, it should be noted that relations between the two countries are much less tense than in Trump’s first term. Then the White House strenuously tried to deprive Maduro of power and put parliament Speaker Juan Guaido in his place. The attempt turned into a failure. Gradually, the protests faded, and Guaido’s ratings dropped. Last year, Maduro won a disputed presidential election, and his legitimacy was not recognized by everyone, even outside the Western world.

However, no one is going to overthrow the Venezuelan president yet. He retains a relatively large amount of support in society, and, most importantly, the law enforcement agencies, and in particular the army, have not turned away from him. Although the economy is in a difficult position, it is supported by oil sales and dollarization.

“There is a lot of pressure on Trump now. He has a fragile majority in the House of Representatives, and Republican congressmen of Latin American descent are demanding that he pursue a tough policy against Maduro. It is quite possible that the United States could achieve a change of power in Venezuela. At least it’s easier than defeating Iran or achieving the annexation of Canada and Greenland. But, apparently, Trump is just not up to it now,” Andrei Shchelchkov, chief researcher at the Center for Latin American Studies at the Institute of Universal History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, told NG.

It is possible, however, that the US president has decided to seriously reconsider his approach to the Maduro regime. In this regard, it is interesting that, as part of the imposition of duties, Trump placed Venezuela in the second group, by no means the most unfriendly countries. The duties against the Venezuelans amounted to only 15%, less than in relation to the EU.

“Under Trump, US foreign policy has become less ideologized. Right now, the president doesn’t really care whether there is democracy in any country or not. The main question is whether you treat Trump well and don’t communicate with America’s enemies. And the main enemy, from the point of view of the US president, is China. He gives money to the Venezuelans, but not for free. Therefore, although Venezuela cooperates with China, the White House understands that relations between Caracas and Beijing are not the easiest,” the expert says.

In general, of the two Latin American regimes that have traditionally irritated the White House (Cuban and Venezuelan), Cuba is of the least interest. She is trapped in a serious economic crisis, and she has no oil. “Venezuela is not forgotten in the United States, although in the context of large-scale events, it is remembered less often. Still, it’s likely that Trump will return to the idea of hitting Maduro. But there is another scenario: two politicians will understand each other and find a common language,” the expert suggests.