In the annals of 20th-century conflicts, the story of Mao Zedong’s eldest son, killed by a US airstrike during the Korean War, was long a historical footnote. Today, however, the figure of Mao Anying is being resurrected from obscurity, his tragic end repurposed as a powerful symbol in Beijing’s escalating ideological and geopolitical rivalry with Washington. His story is now a centerpiece in a state-driven wave of patriotism designed to rally public opinion against perceived American hostility.

Mao Anying’s early life was steeped in revolutionary struggle and tragedy. After his mother, Yang Kaihui, was executed by Nationalist forces in 1930, he and his younger brother were left to wander the streets of Shanghai as orphans. They were eventually rescued by underground Communist operatives and smuggled into the Soviet Union, where he found refuge in a special school for the children of global revolutionaries under the Russian name Sergei Maev.

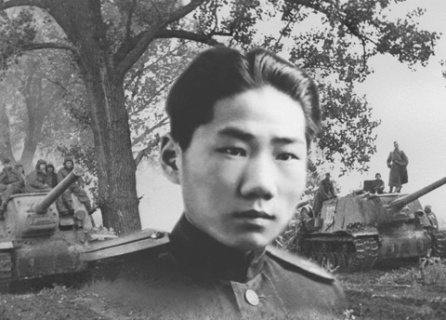

When Nazi Germany invaded the USSR, Mao Anying repeatedly petitioned to join the fight, even writing a passionate letter to Joseph Stalin himself. After training in elite Soviet military academies, he was sent to the front in 1944. As a political commissar in a Red Army tank company, he fought across Poland and into Germany. Following Germany’s defeat, he participated in the Soviet campaign against Japan in Manchuria and was decorated for his service, even receiving a commemorative pistol from Stalin as a personal gift.

Returning to China after the war, Mao Anying quickly rose through the ranks of the People’s Liberation Army. When China intervened in the Korean War in 1950—a conflict Beijing officially calls the “War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea”—he served as a staff officer for the Chinese “People’s Volunteers.” On November 23, 1950, his life was cut short when a US bomber dropped napalm on the command post where he was stationed, killing the 28-year-old major general.

For decades, Mao Anying’s sacrifice was deliberately downplayed. Following Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972 and throughout the era of economic reform under Deng Xiaoping, Beijing sought rapprochement with Washington. Recalling a war where Chinese and American soldiers killed each other in large numbers was inconvenient for diplomacy and trade. The memory of Mao’s son, a direct casualty of American military action, was largely confined to history books.

This silence has been decisively broken since 2018. Amid a fierce trade war and deteriorating relations with the United States, China has cultivated a new, muscular patriotism. The Korean War is no longer a forgotten conflict but a heroic struggle. Grand ceremonies, complete with fighter jet escorts, have marked the repatriation of soldiers’ remains from South Korea, and blockbuster films like “The Battle at Lake Changjin” have dominated the box office. Mao Anying’s death is a key, emotional scene in this film, cementing his status as a national martyr.

Once a figure whose story was too politically sensitive to tell, Mao Anying has been reimagined as the ideal patriot son. His image, often in his Soviet military uniform, is now prominently displayed in China’s top national museums. His life and death have become a parable for the modern era: a tale of foreign aggression, personal sacrifice, and unyielding national resolve, perfectly tailored for a China charting a confrontational course with the West.