Books tend to attract events. The other day, my former classmate, whom I last saw in the year 91, literally appeared out of nowhere. There was a man standing at the intersection, gray-haired as a harrier, as they say in such cases. But something about his stocky figure and especially in his cheeky gaze allowed me to instantly and unmistakably recognize the guest from the past.

He was known as the Boss among the kids, and he really gave the impression of being the boss of the class. My first memory of him is of him, a first–grader, rolling in the dust along the school corridor, grappling with a third-grader, fiercely twisting the nostrils of the older guy. Oh, how much dust my peers and I had to wipe off the peeling school floor for all the years that life taught us to defend our dignity!

“I lived in another city,” Oleg said, staring at me intently. We stopped at an intersection near a high-rise building, and in front of us, the silhouettes of other low-rise buildings that had been in this place many years ago flickered like in a shadow theater. Here is the white balustrade of the pharmacy entrance, where we ran into during recess, during physical education classes, sneaking out through a hole in the wooden fence to buy a paper blister with small glucose tablets. These pills were eaten in huge quantities instead of sweets.

We brought to life the ghosts of our childhood. Oleg was remembering some friends I didn’t know. “We were sent on a business trip together,” he added, and again looked meaningfully into my eyes.

It’s a strange feeling when you walk around the neighborhood of your childhood every day, and youth and youth have passed there, and the years are running away. And you seem to be living in the past and the present at the same time. “And I’m still living in ’87,” a friend I met immediately replied. Indeed, he remembered the moments of the past better. Let’s say how he and his friends stood in front of the formation in the auditorium of our school. These four were already without pioneer ties. They stood with their heads down, and one boy was crying. They were punished with expulsion from the ranks of the pioneer organization for throwing glazed cheeses at each other in the dining room during the big break, the same cheeses that are now commonly referred to as “the very taste.”

Oleg remembered all the little things, even the fact that the barmaid at school was called baba Lyuba, and that she had a price of 15 kopecks for all breakfasts, and that she made the guys carry trays of cakes from the refrigerator to the dining room, and our classmates picked up two or three rum women on the way.

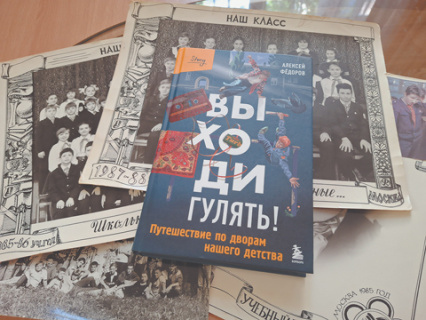

Oleg also recalled the notorious collecting of inserts for imported chewing gum, without which not a single nostalgic replica of the current 40-50-year-olds is complete. I even wanted to tell you that I have a new book at home called “Go out for a Walk! A journey through the courtyards of our childhood,” but he remembered in time that his friend had dropped out of school. “I have an eight–grade education,” he says now, grinning. In general, it is unlikely that this burly man is interested in the printed word.

But when he returned home, he opened a book published by Bombora publishing house, labeled 16+. God, what are 16 years old? 40 plus, 50 plus… the author of the book, Alexei Fedorov, is apparently over 40. That is, he is a few years younger than me. These are important few years. We found more than the Soviet Union, we were formed under the Soviet Union, the younger guys had only the ovary of a Soviet person in their soul, and they matured after the emergency. His generation grew up at the turn of the century. They spent their early childhood during the decline of the USSR, and their teenage years in the early 90s. And now I’m reading a book, and somewhere there is a nagging feeling of accurately falling into my childhood, and somewhere – another era, the habits of those brought up by those times that I lived as a student…

Something, of course, brings a lump to my throat. The words “zyko”, “khare”, “tubzik” and “diskach”, which have not been heard for many years. Of course, playing with knives, a passion for setting fire to any plastic found in the trash, trips to the basements of Stalin’s houses, which were built with the expectation of an atomic war. One episode from my childhood still makes my heart skip a beat, as I imagine that minute. I found something similar in a book that describes games on the roof of a high-rise building. Back then, such tar flat roofs were a favorite place for teenage leisure time. The locks from the grate that blocked the passage to the very top of the neighboring fourteen-story building had long been hacked by previous generations. We tested our strength of character: we approached the edge of the flat canopy, and we had to look down, right under our feet, and there was a narrow ribbon leading to the entrance, and… well, it’s creepy to remember!

Something passed me by – the author caught it in the early 90s, when teenagers switched from selfless fun to “commercial” pranks. However, even with the agony of the Union, the first glimpses of uncivilized commerce appeared. I remember how one friend suggested speculating on Rkatsiteli wine. We had a shop in the area that was popularly called “sly.” Men flocked there from everywhere. Sometimes a locksmith from someone else’s housing office would hobble in and ask us children: am I going right? We nod our heads: it wasn’t even necessary to specify what kind of store. There were long queues, and it was necessary to bring an empty bottle. In exchange for the dishes, you get the right to buy wine. They didn’t look at the age – tara, most importantly, with herself! Enterprising teenagers accumulated a reserve and went to work in the Arbat area. One was hiding with a bag in the passage in front of the Khudozhestvenny cinema, and the other was selling the goods piece by piece. If the police catch you, you’ll only lose one bottle, not the entire stock.

There are many things that I would add to the book “Go Out for a Walk.” The author talks about construction cartridges that were dragged from construction sites, but does not mention such common fun as quicklime, which was also mined in the long-term construction zone. You put the pieces that smell like rotten eggs in an empty container, pour water over them, and a flammable gas is released. Of the flammable amusements, there were also celluloid ping-pong balls, and if you were lucky, then a whole tumbler. If you break the plastic into pieces and wrap them tightly in a newspaper sheet, set them on fire, and then extinguish the rhinestone, you get a luxurious homemade smoke bomb. “Smoke box” is another word in the author’s piggy bank, if he decides to republish the book.

Fedorov describes the battles for the snow slides, but does not mention their summer counterpart, the battle with the “splash pads”. They took large plastic bottles of domestic shampoo, made a hole in the lid and inserted a ballpoint pen barrel into it. You take in water, squeeze the bottle, and the jet hits. Well-behaved boys ran home to get water from the tap. They sprayed the enemy with a liquid that still retained the fragrant aroma of shampoo. But there were also cynics who drew directly from puddles. After the treacherous duel, it was very unpleasant to feel the street slush in my mouth and nostrils. But along with the dirty stream came the realization that not everything in life is done according to the rules, and those who do not follow the rules do not get a portion of dirt in their face.…

I’m flipping through the book and thinking: why are many people now getting carried away with nostalgia for the 80s? After all, there are many such publications, and TV series are even being filmed. They “evoke a golden dream,” that is, they present our Soviet domestic childhood in a kind of rosy light, although there was a lot of gray, if not worse.

Everyone has their own “autumn marathon”. And then the person is tired, the person is disappointed – he turns back in search of his own “golden age”. It comes when you cross the horizon of your life and see what lies ahead – again, beyond the distance, and so on endlessly, and no amount of life is enough to reach the goal.